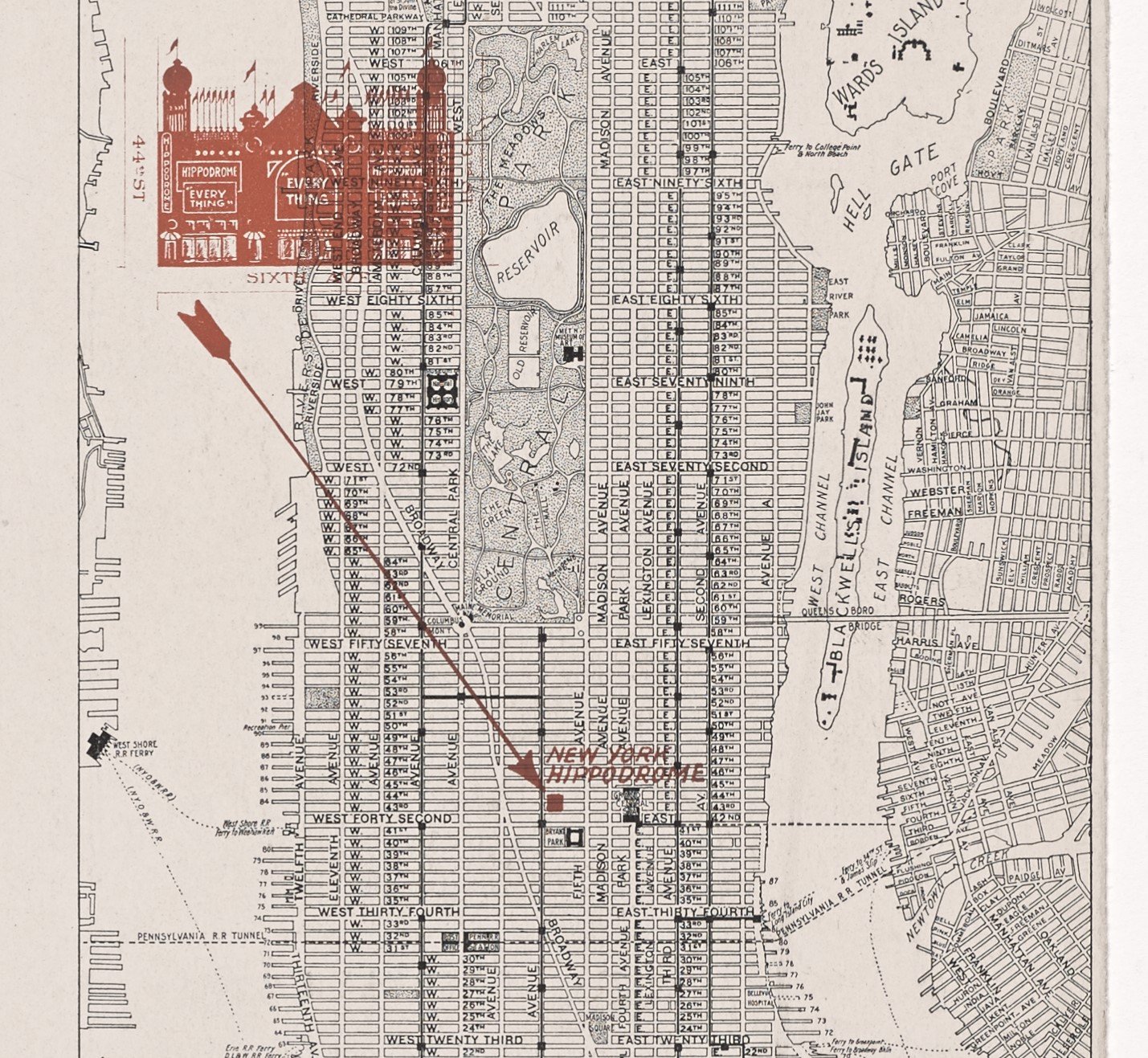

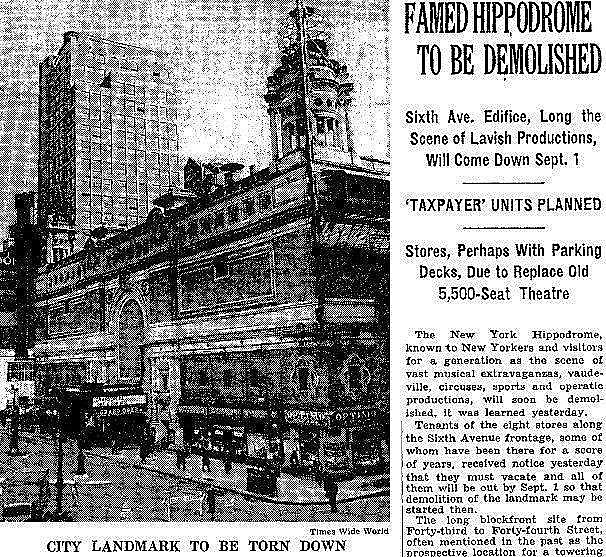

The Masses was a little magazine where labor activists and radical feminists shared space with modernist writers and illustrators. Its roots could be found in the bohemian enclave of Greenwich Village. Editor Max Eastman lived in the neighborhood, as did author John Reed, and painters and illustrators collectively referred to as the Ashcan School because they sketched painted images of working-class New Yorkers. Modernist scholars understand the authors and illustrators of The Masses as a “counterpublic sphere,” one defined less by a shared set of political beliefs and more by the shared impulse to interrogate, mock, and reconsider the pieties and perceived norms of mainstream society. The Hippodrome offered a perfect venue for considering how these norms were communicated to a mass audience. The Masses differed from other modernist little magazines, though, because of the value the publication placed on plain language and everyday life.

Cover for the November 1916 issue of The Masses, via Modernist Journals Project https://modjourn.org/

It makes sense, then, that the Masses drama critic Charles W. Wood would be interested in productions at the New York Hippodrome. Wood does not seem to have been discussed as a drama critic. I found only one instance in the critical conversation on The Masses where his criticism was referenced, where Leslie Fishbein discusses Wood’s review of George Bernard Shaw’s play Getting Married as evidence of the new ideas about romance, sexuality, and family within the magazine. Theater columnist in The Masses and its later incarnation the Liberator, Wood spent much of his career moving between radical and mainstream spheres. While an editor at The Masses, he also wrote for mass-circulation magazines including Collier’s, Forbes Magazine, and Harper’s. His Sunday column in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World featured interviews with business and government leaders. He was an observant Methodist (the W. stood for Wesley) who friends remember as deeply funny and eager to shock the narrow-minded moralists of the day. Wood begins his first column by disavowing what we might think of as the objectives for a theater column:

“the purpose of this new department in The Masses is to provide me with free tickets to New York theater. I am not a dramatic critic. I’m a long way from being a dramatic critic. But then, the New York shows are a long way from being drama. New Yorkers don’t want drama; they want shows. “His Wedding Night with the Dolly Sisters” is just the thing New Yorkers want to see. They let such a piece of supreme dramatic art as The Weavers struggle along for a few weeks and go broke. ”

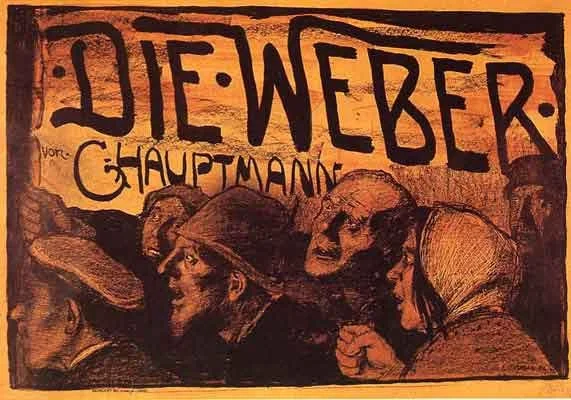

The Weavers is an experimental Gerhard Hauptmann play where weavers protest as a mass against the Industrial Revolution, which Wood calls “a piece of supreme dramatic art.” Here’s a poster from the original production:

A poster from the original production of The Weavers in 1897 via Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Die_Weber_1897_by_Emil_Orlik.jpeg

But that play does not have the same popular appeal as the show the New York Times called a “frisky farce,” where dancing twin sisters bamboozle a hapless groom on his honeymoon. Where New Yorkers might admire the sentiment or pedigree of the former show, that admiration does not translate into action.

White Studio - New-York Tribune (New York [N.Y.]), June 4, 1916 https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83030214/1916-06-04/ed-1/?sp=13 Via Wikimedia

Notice how much the Masses cover goes for the same aesthetic as this promotional picture of the Dolly sisters: stylized young white woman’s beautiful, symmetrical face(s) against an abstract background. The socialist signs on the magazine cover are relatively subtle — cossack hat implied over her mass of black hair, red background — but the image is still beautiful in a conventionally appealing way. And this to me is the central question at work in Wood’s discussions of Hippodrome performances, which I will talk about in a later post and in the chapter I’m working on. What kind of conventional aesthetic appeals do people need in order to lower their defenses and maybe start thinking about politics? How can you make art that is both a pleasure to look at and something that appeals to a higher moral purpose? He thinks about those questions through the surprising juxtaposition of ballet and ice skating. But I’ll have to save that for next time.