Wow, it’s been a minute. I just got back from the Modernist Studies Association conference, where I presented some ideas on the Hippodrome and its relation to modern leisure transportation. I’m including an edited version of my talk and slides below.

The Hippodrome interior spaces put the audience members in the mind of circus goers (with sculpted elephant head sconces and relief sculptures of horse drawn chariots) but took them even further afield with the first extravaganza called A Yankee Circus on Mars. Martian airships and “automobiles” for chorus girls drawn by elephants let the audience know that fantastic mobility was central to the Hippodrome’s aesthetic.

Detail from O’Sullivan, Burns. Untitled (A Yankee Circus on Mars) : Drawing, Undated. The New York Hippodrome : Drawings, 1905-1908. 1905. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:495365297$1i. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, MS Thr 1716 (Folder 1). Accessed 6 Oct. 2022.

Looking at Hippodrome programs from the early 1910s, we can see that the Hamburg American Line regularly advertised their cruises on the inside front covers. In one case, the headline for the advertisement echoes that of the show. Of course, both would have made audiences think of Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days. Under the artistic direction of Arthur Voegtlin, Hippodrome shows in this period moved away from the imagined and historical landscapes that had previously been staged. They became more like travelogues, with a perfunctory plot (stolen diamonds, stolen maps) inciting the travel and offering the ostensible reason for changing scenes. In fact, we might consider the plots of shows like these to offer a kind of imaginary passengering, one that compensates for the slowness of travel and the encumbrance of geography. The show Around the World, for example, shows characters departing from New York City, arriving in England, then going to Switzerland, Egypt, Constantinople, India, Italy, Spain, Hawaii, and then to Ireland where a diamond that grants bad luck to whoever owns in is thrown down a well at “Blarney Castle.”

Inside front cover of Around the World program, Arthur Voegtlin Collection, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

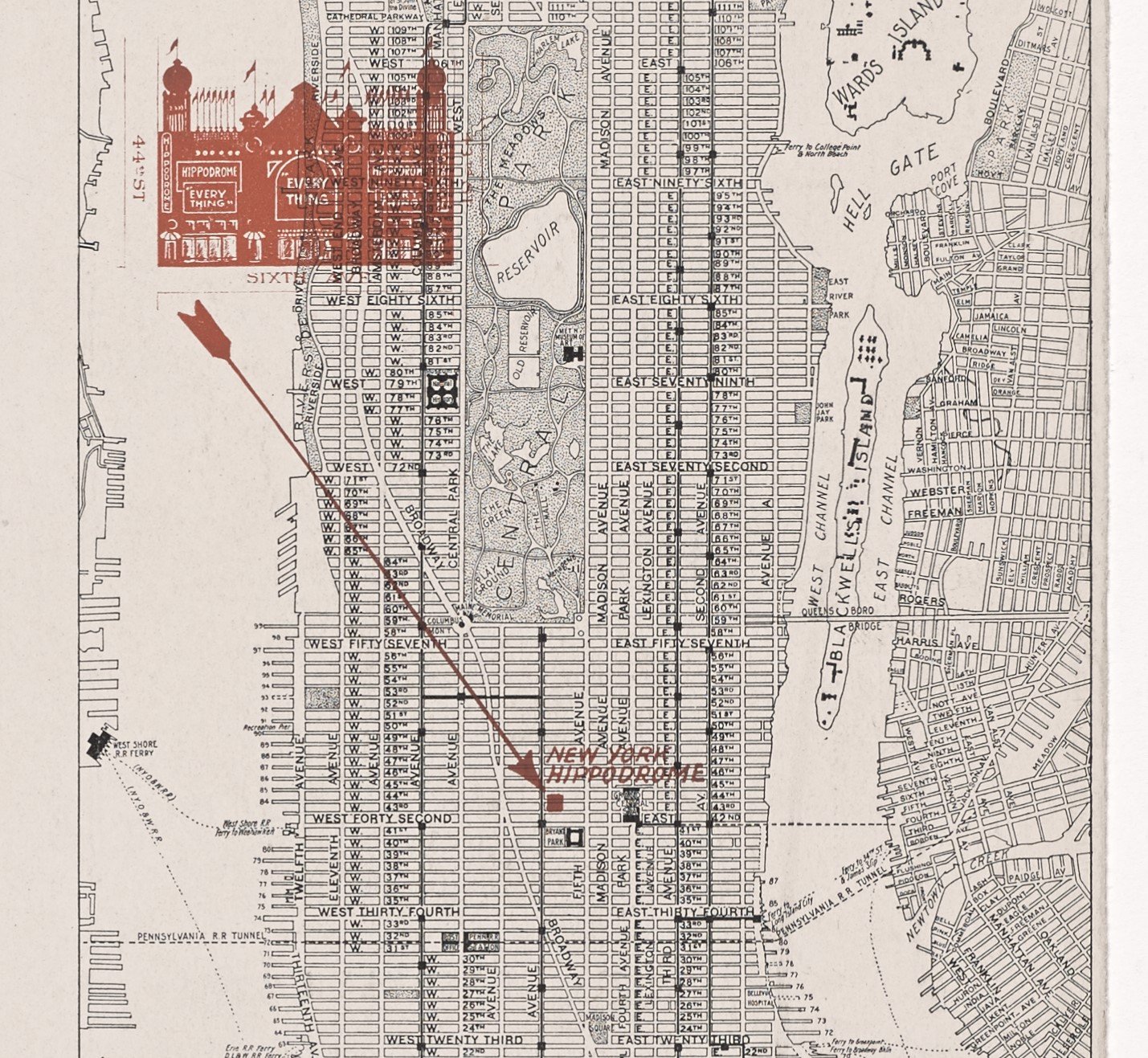

Moving in to a new phase of Hippodrome spectacles, under the management of Charles Dillingham, we can see in this promotional subway map for the 1918 show Everything an appeal to a new kind of tourist – a local passenger from the outer boroughs. We can see maps that show the appropriate stations for reaching the Hippodrome on the Interborough Rapid Transit subway system, the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit subway system, and the Interborough elevated train lines. The slogan on the front cover – “If You Haven’t Seen the Hippodrome, You Haven’t Seen New York” – seems designed to counteract the local resident’s pride in avoiding tourist sites.

Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. "New York City subway map with Everything cover" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1918 - 1919. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/822ed850-61fe-0132-7188-58d385a7b928

Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. "New York City subway map with Everything cover" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1918 - 1919. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/822ed850-61fe-0132-7188-58d385a7b928

And the page where the Hippodrome theater is highlighted on its Manhattan map shows just how excessive the spectacle is meant to be. The theater is bright red on a black and white map, more obtrusive that the station markings on the other pages, and it’s so large and displaced from its actual geography that it’s parallel to Central Park and halfway into the Hudson River. All of these traces of the Hippodrome’s passengering practices that remain on paper suggest a kind of dislocating, escapist spectacle, one that ties in to existing networks of travel communication and that redefines even locals of the unified city as potential tourists.