So if you read anything about precision dance and chorus lines in the 1920s, you’ll come across the Tiller Girls. They were a British troupe of performers, trained by John Tiller to dance in unison. You can see one of their routines on Youtube here:

The Tiller Girls made a big splash in the U.S. when they appeared in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1924. But in his book Tiller’s Girls (London: Robson, 1988), Doremy Vernon notes that “although reporters gave the impression that the troupes were new to the American stage, they had in fact made their debut as far back as 1900 when George Lederer booked them to perform their original Pony Trot.” The “Pony Trot” number was part of Lederer’s 1899 spectacle The Man in the Moon. Actress Zella Frank performed “The Jockey Chorus” supported by “The Pony Ballet.” The group of sixteen petite dancers moved across the stage in pairs, as if they were horses pulling a carriage.

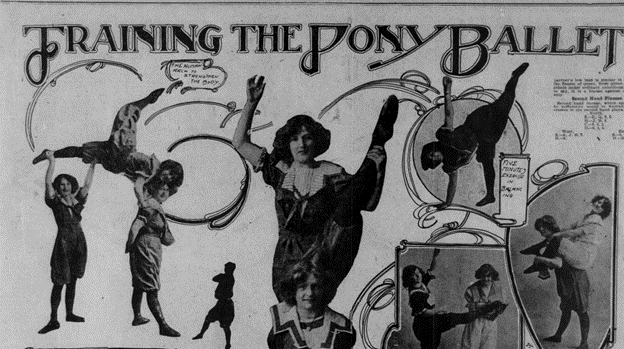

A few summers later, another group of English performers came to the U.S. under the same name, this time without Tiller at the helm. This group earned a feature spread in an April 1902 Sunday edition of the San Francisco Call, including ample illustrations of their acrobatic skill.

Headline “Training the Pony Ballet” appears above arrangements of young women in a “human arch,” one standing on the shoulders of another and holding up her leg, and other acrobatic poses.

The Pony Ballet set off a trend among Broadway dance directors. Ned Wayburn and Gertrude Hoffmann were especially known for their choreography using Pony Ballet-style choreography. And according to a column in Variety called “‘Corks’ on Girl Acts,” by December of 1905 some people were sick of it. There’s a funny account of a burlesque producer who wants to go back to the good old days when a beautiful pair of dancers did a “sister act.” Instead he sees all kinds of “girl acts”:

“I don’t know where Ned got his ideas in the first place, but they are all about the same, and the rest follow along until you get the idea that some one hired a whole orphan asylum and taught all the girls at once. There’s the same stamping, the same hand-clapping and all that, and except for the name and the costumes, one act is the same as the other whether Weytburn or Gertie Hoffmann or someone else put ‘em on. They can’t pay the girls a fair salary and make a profit out of ‘em, because a manager won’t pay enough, and so they do the best thy can, and they best they can is rotten.”

One of the reasons I started my Hippodrome project was to figure out what life was like for the chorus members. I keep finding all sorts of choruses in this era, and I want to know more about all of them!